James Webb telescope confirms there is something seriously wrong with our understanding of the universe

“Astronomers have used the James Webb and Hubble space telescopes to confirm one of the most troubling conundrums in all of physics — that the universe appears to be expanding at bafflingly different speeds depending on where we look.

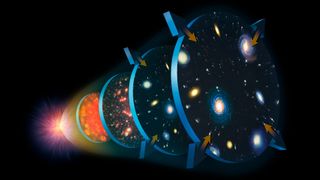

“Astronomers have used the James Webb and Hubble space telescopes to confirm one of the most troubling conundrums in all of physics — that the universe appears to be expanding at bafflingly different speeds depending on where we look.This problem, known as the Hubble Tension, has the potential to alter or even upend cosmology altogether. In 2019, measurements by the Hubble Space Telescope confirmed the puzzle was real; in 2023, even more precise measurements from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) cemented the discrepancy.

Now, a triple-check by both telescopes working together appears to have put the possibility of any measurement error to bed for good. The study, published February 6 in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, suggests that there may be something seriously wrong with our understanding of the universe.

Related: After 2 years in space, the James Webb telescope has broken cosmology. Can it be fixed?"With measurement errors negated, what remains is the real and exciting possibility we have misunderstood the universe," lead study author Adam Riess, professor of physics and astronomy at Johns Hopkins University, said in a statement.

Reiss, Saul Perlmutter and Brian P. Schmidt won the 2011 Nobel Prize in physicsfor their 1998 discovery of dark energy, the mysterious force behind the universe's accelerating expansion.

Currently, there are two "gold-standard" methods for figuring out the Hubble constant, a value that describes the expansion rate of the universe. The first involves poring over tiny fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background (CMB) — an ancient relic of the universe's first light produced just 380,000 years after the Big Bang.

Between 2009 and 2013, astronomers mapped out this microwave fuzz using the European Space Agency's Planck satellite to infer a Hubble constant of roughly 46,200 mph per million light-years, or roughly 67 kilometers per second per megaparsec (km/s/Mpc).

The second method uses pulsating stars called Cepheid variables. Cepheid stars are dying, and their outer layers of helium gas grow and shrink as they absorb and release the star's radiation, making them periodically flicker like distant signal lamps.

As Cepheids get brighter, they pulsate more slowly, giving astronomers a means to measure their absolute brightness. By comparing this brightness to their observed brightness, astronomers can chain Cepheids into a "cosmic distance ladder" to peer ever deeper into the universe's past. With this ladder in place, astronomers can find a precise number for its expansion from how the Cepheids' light has been stretched out, or red-shifted.

Related: Mysterious 'unparticles' may be pushing the universe apart, new theoretical study suggests

But this is where the mystery begins. According to Cepheid variable measurements taken by Riess and his colleagues, the universe's expansion rate is around 74 km/s/Mpc: an impossibly high value when compared to Planck's measurements. Cosmology had been hurled into uncharted territory.

"We wouldn't call it a tension or problem, but rather a crisis," David Gross, a Nobel Prize-inning astronomer, said at a 2019 conference at the Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics (KITP) in California.

Initially, some scientists thought that the disparity could be a result of a measurement error caused by the blending of Cepheids with other stars in Hubble's aperture. But in 2023, the researchers used the more accurate JWSTto confirm that, for the first few "rungs" of the cosmic ladder, their Hubble measurements were right. Nevertheless, the possibility of crowding further back in the universe's past remained.

To resolve this issue, Riess and his colleagues built on their previous measurements, observing 1,000 more Cepheid stars in five host galaxies as remote as 130 million light-years from Earth. After comparing their data to Hubble's, the astronomers confirmed their past measurements of the Hubble constant.

"We've now spanned the whole range of what Hubble observed, and we can rule out a measurement error as the cause of the Hubble Tension with very high confidence," Riess said. "Combining Webb and Hubble gives us the best of both worlds. We find that the Hubble measurements remain reliable as we climb farther along the cosmic distance ladder."

In other words: the tension at the heart of cosmology is here to stay.”